This blog post originates from a conversation on a morning ride down to an archaeological site in a pickup with the site director: during the night before, I’d just been able to send him the link to the results of the virtual tour of his site that I made, and when he picked me up that morning, he seemed concerned. I asked him what was wrong, and, reader, this is completely true: the very tough and brusque site director started crying in the truck with me. He said, “We had professional 3d scan teams come and scan for months and months, and we couldn’t access any of their results without going to the United States. With your virtual tour, we can finally see all our work.”

Needless to say, I was touched. And really grateful that they would benefit from the work building a virtual tour that I and the whole team on site were making. But the other team before me (who will remain anonymous like everyone in this story) were world class at 3d scanning and deserve a ton of respect for their work! Many 3d captures are so comprehensive and professional that they become nearly impossible to share without specialized computers–much less to the communities where they originated.

The scans the previous team had created were deeply important for research–but not accessible in the way that the site director had expected when he commissioned the scan.

I can’t tell you how many similar–though maybe less emotional–conversations I’ve had like this over the past two years. A lot of confusion originates from the term, “Virtual Tour.” People tend to use this word to mean anything from a gallery of photographs to a video recording to an entire 3d scan of a space that genuinely results in terabytes of data requiring supercomputers to process.

If you’ve been working at a museum, gallery, or heritage site recently and might not be familiar with the morass of 3d technologies and how they differ, you’re in good company: they’re enough to make anyone’s head spin! I’m hoping this can be a guide to show some specific examples of the different types of virtual tours so that you can make your own decision about what’s best for your space.

Also it’s worth mentioning: in the past, we’ve written about virtual tours and digital exhibitions, both an overview of types of virtual tours and how they may be used as a tool for accessibility to your spaces among other topics. This post narrows in to compare different technologies and their respective outcomes in detail so that when you capture your space to make a digital version in some way, you’ll know what you’re getting.

So what’s the difference between virtual tours, 3d scanning, and photogrammetry?

If virtual tours essentially refer to any way of representing a physical space digitally, then 3d scanning and photogrammetry are methods of creating virtual tours along with video walkthroughs, image galleries, and several other creative methods. Video walkthroughs and image galleries are sometimes important, but I would argue that they don’t offer very sophisticated experiences compared to virtual renderings in 3d which are more engaging for many users.

If you’re interested in making a 3D virtual tour of your space, then, you need a method of 3d capture. The history of creating replicas of real-world objects in 3d goes back as far as even Ancient Egypt (a time near and dear to your author’s heart), one may argue, where artisans would create plaster casts of the deceased to remember them. In contemporary times, we now either use high-powered lasers to make a 3d copy of a space or take many (maybe thousands) of 2d photographs of a space to feed into a computer and get a 3d rendering on the other side via a process called photogrammetry. If you’ve seen the new Lion King for instance, the whole environment in the movie was created from real plants and other objects captured with photogrammetry.

So I’ll start with the laser scanners since that’s the conversation that brought about this post.

What are 3d Laser Scanners and What are Their Results for Museums and Heritage Sites?

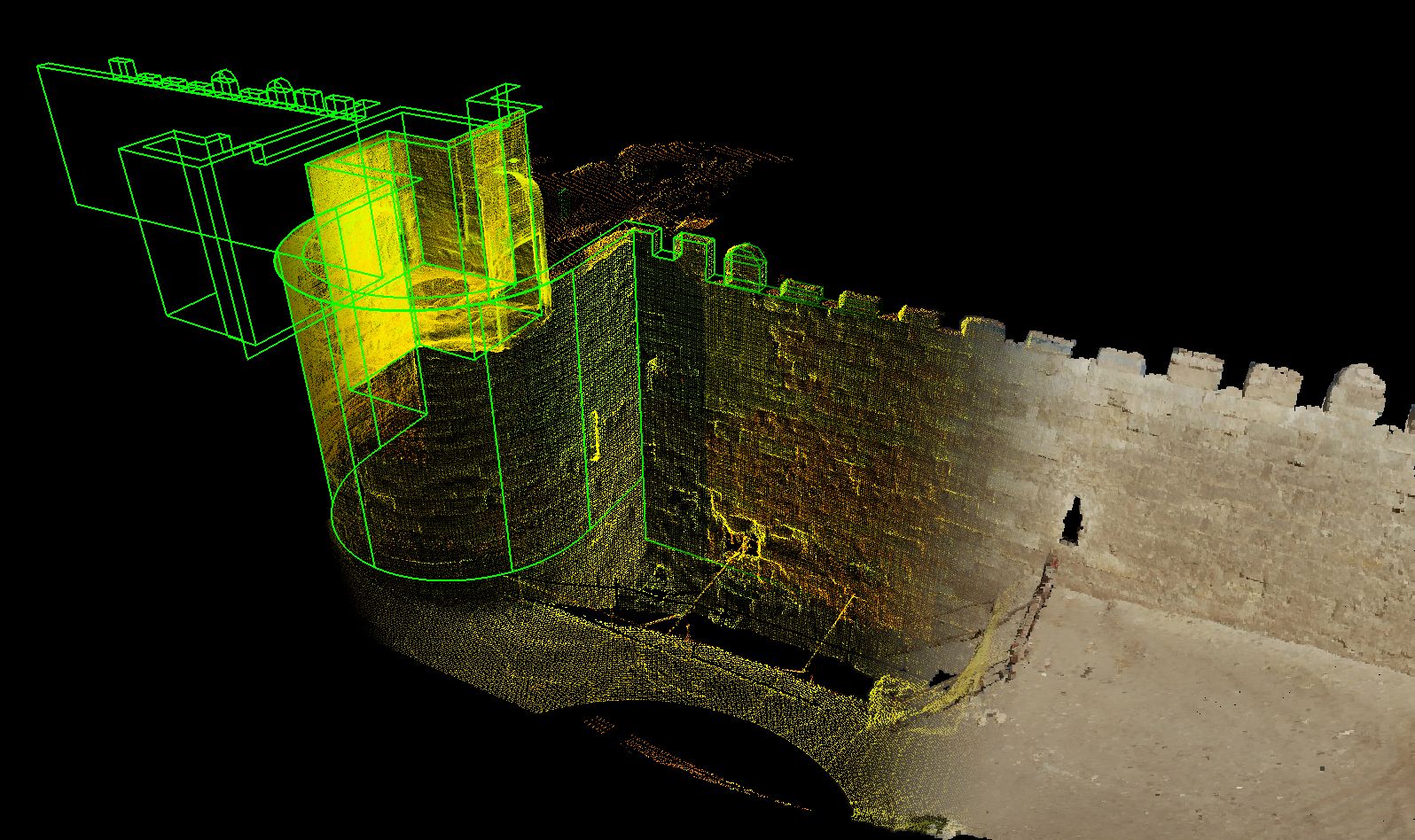

The most sophisticated of 3d scanning technology out there currently are 3d laser scanners. It kind of works like this: the scanner shoots a laser beam at an object, a wall say, and it can understand the distance that it is from the wall by measuring the amount of time that it takes for the laser to bounce off of the wall and back to the scanner. Now imagine that you’re shooting millions of lasers at the entire environment and taking millions of points about your surroundings, and you start to have a pretty detailed 3d model of whatever space you’re in.

This is called Lidar: short for “light detection and ranging” – basically just the laser thing from the previous paragraph. You may have heard of it before because the new iPhones have a Lidar laser scanner in them that they use to understand the environment and create fancier photo and video effects. You can also use this to make your own 3d captures if you have an iPhone with Lidar, but more on that later.

In order to create the highest fidelity 3d model possible, 3d Laser Scanners get really advanced–like think in the order of hundreds-of-thousands-of-dollars-per-scanner-type advanced. And they’re able to create precise 3d models of real world spaces at a level of detail that’s unparalleled by other methods for a lot of technical reasons.

This is great for researchers for the purposes of studying things like if a tessera in a mosaic shifts place or a column is in danger of falling over. It’s also really important for preservation of heritage sites around the world to have these laser scans since these sites are damaged and destroyed all the time, and by using the 3d data, archaeologists and conservators can sometimes prevent damage before it occurs–or at least have a record of what was.

The catch with this highly detailed data is that when it comes to using this for the purposes of teaching or making a virtual tour, it’s often in such large files, it’s impossible to send over the internet and even requires special computers to be able to view it. For larger sites, think in the 100s of gigabytes at least–if not more.

This is the conundrum that the site director from the start of this post was in: his site was captured with highly detailed laser scan data that was essential to research and preservation–but the data could only be viewed in the United States and wasn’t able to be used for teaching the local community about the site at all.

Thankfully there are different types of laser scanners–and new tools for sharing the results–so that this doesn’t have to always be the case.

Matterport: An Alternative Laser Scanner and Method of Sharing Laser Scan Data

Luckily for us, an alternative laser scanner and way of sharing large laser scan datasets exists to create virtual tours for the purposes of teaching and informing the general public–along with meeting some goals of conservation and preservation. While I’m simplifying a lot of details, the alternative tools that in practice we’ve seen preferred and used the most by general public users for virtual tours is Matterport.

For the 3d scanning community, Matterport are relative newcomers focused mainly on the real estate market–if you’ve bought a house in the last few years, chances are that you saw one of their virtual tours of the house before you purchased it. As a result, Matterport’s cameras and technology is focused much more on ease of capture and sharing of the data instead of research recording.

Matterport calls the results of their capture a “digital twin”. From their website, they describe a digital twin like this:

A digital twin is a digital copy of a real-world place or object. Artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies enable the creation of digital twins, which are dimensionally accurate 3D digital models that can be updated quickly to reflect changes with its physical counterpart.

Matterport has particularly caught on with museums showcasing their collections because the 3d scanning space capture is inexpensive–and again really useful to share to the general public.

Matterport has quite a bit of secret sauce that makes them easy to use by general public users. When users walk around in a first-person view, they see a photorealistic experience by viewing a 360 image instead of the 3d data directly but can always switch the view to see a low resolution 3d model or floorplan. It all works kind of like Google StreetView so even people who aren’t very technically literate can figure out how to use it.

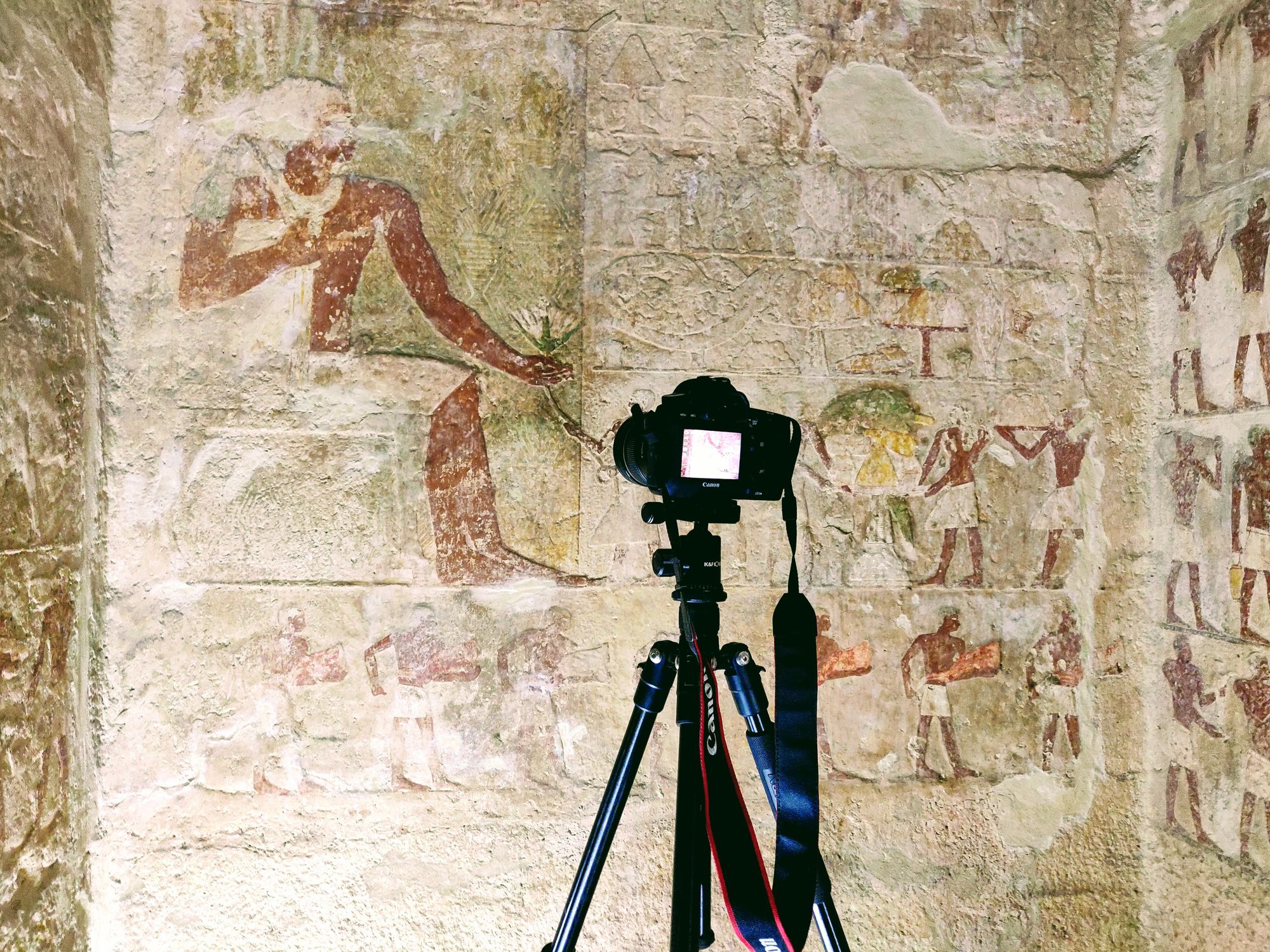

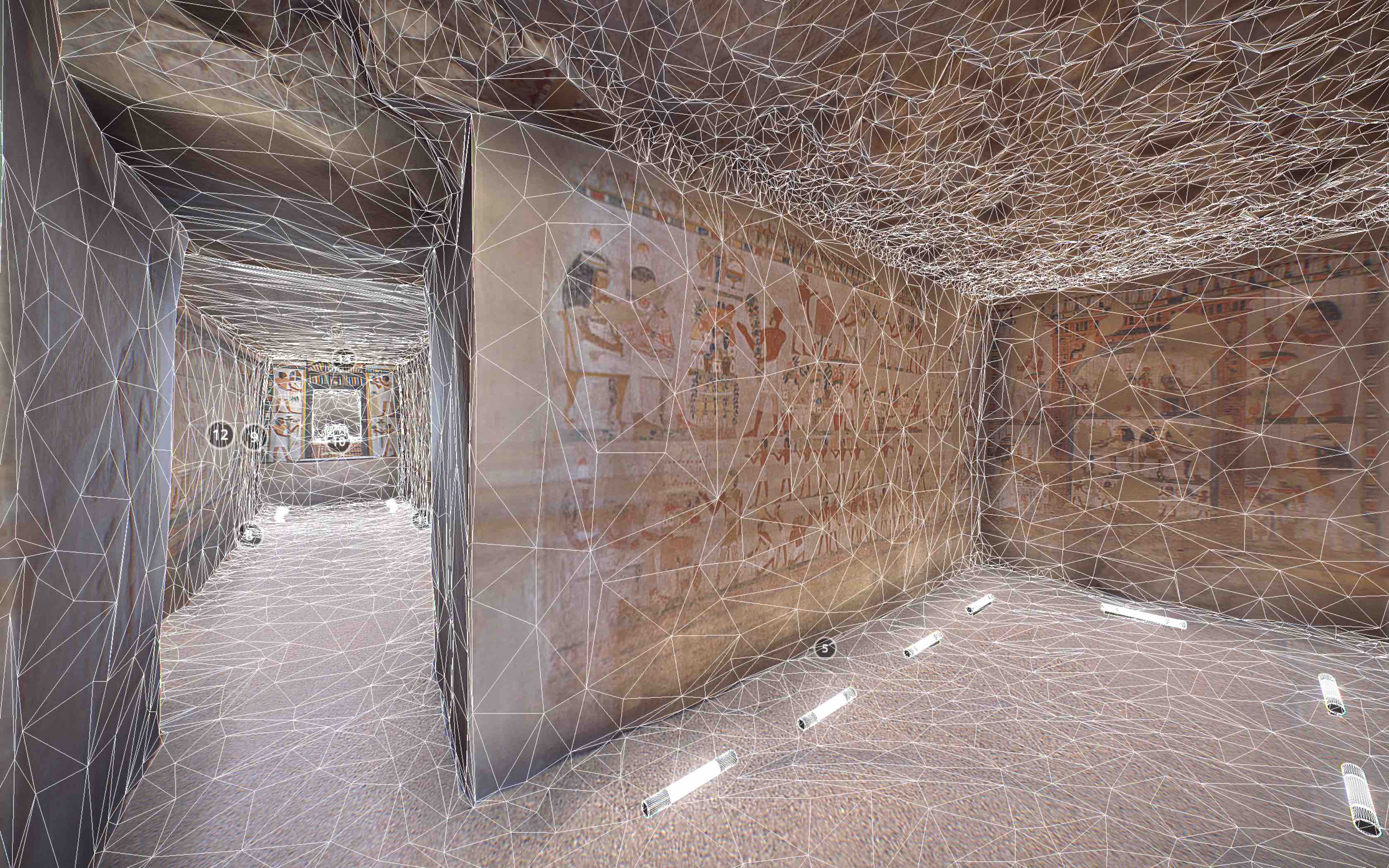

Here’s an example showing the switch between the 3d model and the 360 images from the Tomb of Menna, a space I 3d scanned with Matterport and captured photogrammetry for:

No special apps or computers are needed for viewing Matterport spaces like this, and they even work on low bandwidth internet connections and older smartphones. As a result, teachers and students especially all over the world–and on varying sides of the digital divide–can access the photorealistic Matterport scans and tour the heritage sites and museums that are recorded on the platform.

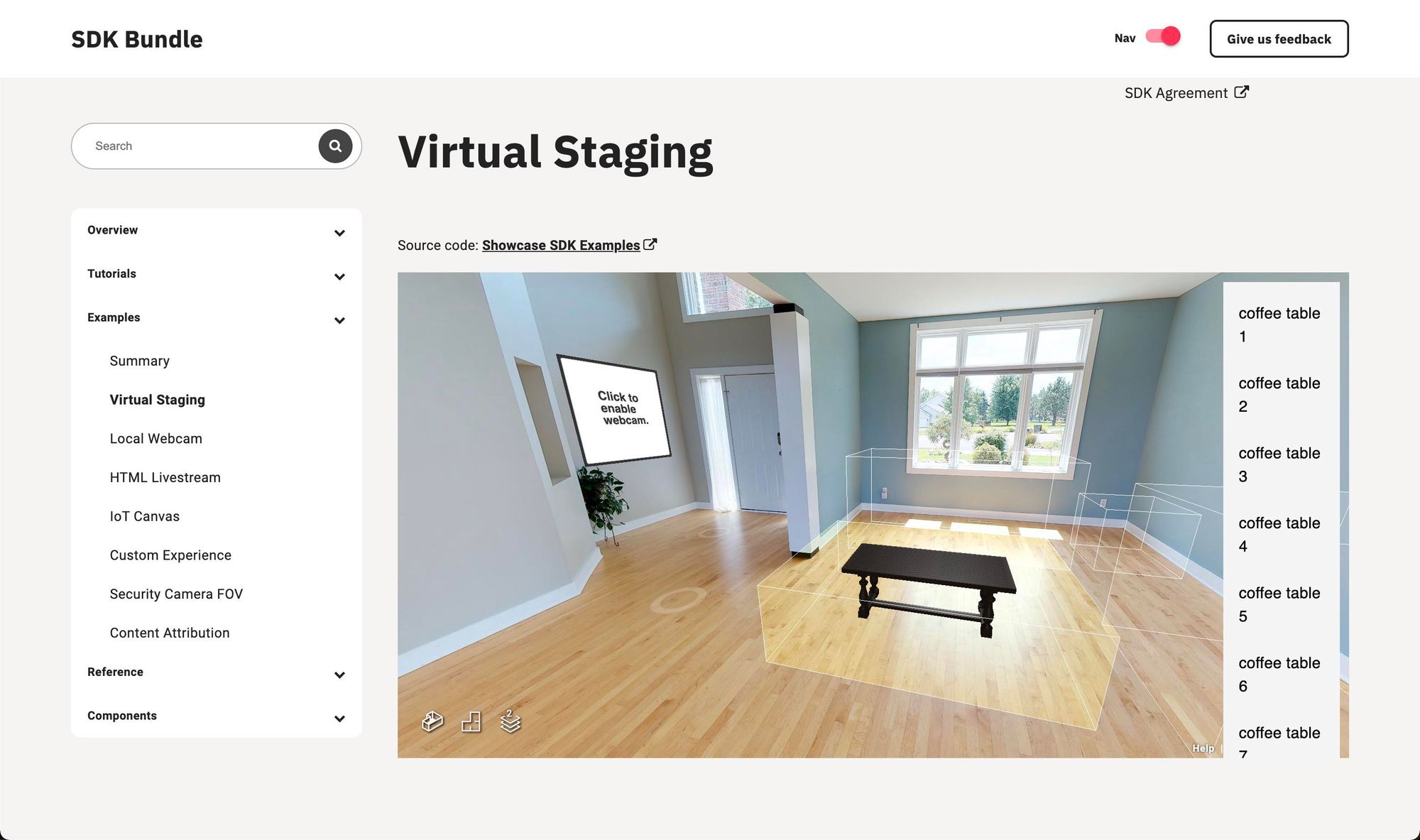

If you’re a more advanced 3d team building with Matterport and want to say, put in more detailed information or other 3d models for historical reconstruction or animations, you have the flexibility to do that also through the Matterport SDK. I’ve been building with this in recent months, and it’s stable and easy to use.

You can see some of their custom experiences on the documentation page for an example of what’s possible.

3D Capture for Research and Scholarly Publication Purposes

While writing this, I want to mention that several of my peers in academic 3d capture technologies would not have a preference for Matterport because they’re more focused in generating high-quality 3d capture data and don’t see the value of Matterport’s switching between 360 images and the 3d model like I describe. I want to validate this and give their opinion voice in this post because it’s true: for research and scholarly publication purposes, there are many methodologies in capture and display that are more highly detailed and more important. And they’d possibly argue that capturing and sharing data with Matterport is less serious or scholarly.

Some people that have this position come from the 3d researchers that need to apply for funding for doing critical 3d capture of monuments that are falling apart to determine if a column is going to topple, a wall is going to collapse, and heritage is going to be lost. If funding agencies suddenly see that 3d capture and display with a different platform like Matterport is 1/10th of the price, they are less likely to fund the higher-resolution scholarly research capture–without knowing the difference in the results.

Also 3d professionals that want the highest resolution 3d model of a given space possible would prefer to use higher fidelity and more expensive 3d scanners and photogrammetry. This enables the high quality 3d models to be used in other applications such as in history-themed video games and the like.

Ultimately each of these different methods are very useful for different purposes and should be evaluated independently from each other since there’s such a wide range in 3d scanning technologies. That being said, each 3d scanning team that captures a bunch of data needs a workable plan for sharing that data with the communities where the data originated.

Here’s the same tomb as the last section shown on Sketchfab instead of Matterport:

A good option for sharing 3d capture data from 3d scanning and heritage technologies is Sketchfab. The Sketchfab website lets you share 3d models and has a huge cultural heritage and history section.

There’s no 360-photograph-to-3d-model transition and the first-person view is off by default and much trickier to use, so people who aren’t super technical or academic researchers themselves sometimes have a harder time exploring large spaces on Sketchfab. But you can rotate and zoom into the high-fidelity 3d models to see an entire wall at once at exactly the angle that you want to see it as.

After the high resolution capture, you’ll need to process the 3d model files to get a version that’s small enough to be easily shared on a website and viewed on a laptop or mobile device. This involves a 3d artist working through a complex technical process to manually make the 3d capture a much smaller filesize using several different steps and methods. Some tools make automating this step easier now, but as of writing, there’s no substitute for a lot of hours of human intervention needed to process a high resolution 3d capture to the filesizes needed for sharing on Sketchfab.

Virtual Tours, 3D Scanners, and Photogrammetry have widely different results: you can choose which one is right for your heritage site or museum

So if you’re considering 3d scanning for your museum or heritage site, you can understand what to expect from each different type of result of high resolution 3d scanning to Matterport digital twin captures.

If you’re working on conservation, preservation, or other research purposes, you may need a very high fidelity laser scanner or photogrammetry capture to record as much data as possible. It will likely be challenging to share that data through a website but definitely not impossible.

For example, in the specific case of the Tomb of Menna, the budget for the version published on Sketchfab and Google Arts & Culture was 20x the budget of the Matterport capture. But around 600x more people visited the Matterport model than the Sketchfab model.

So if you’re capturing for educational purposes to share your space with the general public, you might choose a platform like Matterport for a first person walkthrough of your space that’s accessible to the greatest number of people possible around the world.

And finally, no matter what 3d platform you choose, if you’re building spaces with Matterport or Sketchfab and want a guided tour, scavenger hunt, or in-depth stories told alongside your spaces, maybe with an integrated museum collections interface, Mused is a great tool to build these experiences with! You can reach your users and keep them engaged, asking questions, and learning about your site to build your community around your collection.

This is a big topic–and much more detailed comparisons could still be made. I’d love to continue the discussion with any thoughts you may have about this if you want to write in on the comment or email us directly at [email protected]!

1 comment

Comments are closed.